Which Is More Secure: Face ID, Touch ID, Optic ID, or a Passcode?

Posted on

by

Kirk McElhearn and Joshua Long

When Apple introduced Touch ID, the company told us that it was secure. Apparently it’s secure enough that financial institutions trust it for authentication, both with Apple Pay and with many banking apps. The same is true for Face ID, as well as Optic ID, used on the Vision Pro. But how secure are these technologies, really?

In this article, we’ll look at each of the three methods of authenticating on Apple devices: Face ID, Touch ID, Optic ID, and a passcode. And we’ll discuss which is the most secure, and why.

In this article:

- How secure is Face ID?

- What about Touch ID?

- How secure is Optic ID on Apple Vision Pro?

- Other Face ID and Touch ID considerations

- How secure is a passcode?

- Key takeaways

- How can I learn more?

How secure is Face ID?

Apple introduced Face ID in 2017 with the iPhone X. It is current available on all iPhones other than the iPhone SE, and iPad Pro models, starting with the 2018 3rd generation iPad Pro. Face ID doesn’t just take a photo of your face. It works with two elements. First, the TrueDepth camera projects more than 30,000 invisible dots on your face to create a depth map. Second, it also captures an infrared image of your face. The neural engine of the iPhone’s or iPad’s chip combines these two elements. Apple’s documentation states that it “transforms the depth map and infrared image into a mathematical representation and compares that representation with the enrolled facial data.”

As the successor to Touch ID, Apple claims that, “The probability that a random person in the population could look at your iPhone or iPad Pro and unlock it using Face ID is less than 1 in 1,000,000.” However, Apple also points out that, “The statistical probability is higher […] for twins and siblings that look like you, and among children under the age of 13 because their distinct facial features may not have fully developed.”

Require Attention for Face ID

Face ID includes a built-in attention awareness feature. This setting is called “Require Attention for Face ID;” it’s enabled by default (unless you enabled VoiceOver during initial setup). When Face ID checks whether it recognizes you, it also tracks your eyes to determine whether or not you’re looking at the screen. Apple Pay and other authorizations are only granted if you’re looking at the device.

It’s important to note that users may choose to disable attention awareness; this is sometimes necessary for accessibility reasons. Disabling this functionality means that you don’t need to look directly at the screen to use Face ID. In rare circumstances, having attention awareness turned off can be potentially problematic; if someone holds your device near your face against your will, your device may unlock even if you avoid looking at it.

Next, let’s look at a couple of optional trade-offs between security and convenience: Face ID with a Mask, and Unlock with Apple Watch.

Face ID with a Mask

Apple “enhanced” Face ID during the COVID pandemic so it can work when you’re wearing a mask. Although this is more convenient, it significantly reduces the security of Face ID. There are two variations of this technology, both of which can be found in Settings > Face ID & Passcode. If you have an iPhone 12 or later, you can enable the setting Face ID with a Mask. Apple says that this relies on “unique facial features around the eye area to authenticate,” which means there’s a higher probability of a false positive. Again, this is especially true for a close blood relative. Unless you still need to wear a mask, it’s a good idea to turn this feature off.

Unlock with Apple Watch

The second way to unlock your phone while wearing a mask, which doesn’t require a specific iPhone model, is Unlock with Apple Watch. If your Apple Watch is unlocked and on your wrist, and within a few feet of your iPhone when you try to use Face ID to unlock your phone, your watch will unlock your phone instead of a partial-face Face ID match. Technically, this bypasses Face ID and shifts the authentication burden to your watch instead—which means you are only unlocking your phone; you cannot use Face ID in other apps while wearing your mask (unless you also have the other feature enabled).

If someone near you picks up your iPhone, and if they’re wearing a mask or covering their face, your Apple Watch might unlock your iPhone for that other person. If you’re paying attention and react quickly, your Apple Watch will tap your wrist and give you a “Lock iPhone” button.

The “drunk in a bar” scenario, Face ID edition

Another weakness of Face ID is if someone is intoxicated, another person could hold the owner’s device in front of their face. A quick glance from the device owner would be enough to unlock it without them being aware.

It’s fair to say that Face ID is extremely secure, unless you’re likely to be in a compromising situation where you could be tricked into looking at your iPhone—or you have a twin or a very similar-looking family member. Tests have shown that with twins, at least, Face ID simply can’t tell the difference.

The verdict on Face ID

Face ID score: 9/10

Caveats:

- much less secure if you have a twin—or a parent, sibling, pre-adolescent child, or other close relative—who looks a lot like you

- a highly skilled attacker could theoretically fool Face ID with a spoofed facial model/mask

- however, this is significantly harder than fooling Touch ID with a spoofed fingerprint

- law enforcement or a thief may compel or trick you into looking at your phone up close to unlock it

- if you’ve turned off the “Require Attention for Face ID” setting, you may not even have to look directly at your device to unlock it

- a thief could force you to unlock your device with threats of violence

- insufficient protection if you have a well-funded or well-connected adversary (e.g. a nation state)

How secure is Touch ID?

Touch ID dates back to 2013 with the release of the iPhone 5S, and was added to iPads starting in 2014. Currently, the only iPads with Touch ID are the iPad Air, the iPad Mini, and the basic iPad (10th generation). The same technology is also available on many Mac models from 2016 to the present: the MacBook Air, MacBook Pro, and Mac models with the Magic Keyboard with Touch ID.

Touch ID doesn’t just take a fingerprint; it “take[s] a high-resolution image from small sections of your fingerprint from the subepidermal layers of your skin […] then intelligently analyzes this information with a remarkable degree of detail and precision.”

With both Face ID and Touch ID, iPhones and iPads don’t store photos or fingerprints. Apple says that Touch ID “creates a mathematical representation of your fingerprint and compares this to your enrolled fingerprint data to identify a match and unlock your device.” In addition, with both of these technologies, the mathematical representation is refined over time, as you use them.

With Touch ID, the probability of a random person unlocking your device on the first try is 1 in 50,000. Twins and siblings have no advantage, since their fingerprints don’t resemble each other. Touch ID is also secure enough for banks and payment processors to trust it.

Historical attacks on Touch ID

However, security researchers have found that Touch ID and other fingerprint authentication technologies can be defeated fairly easily. Hackers quickly found ways to bypass Touch ID shortly after its release. Researchers have found that other methods, such as 3D printing, can fool similar technology. For the latter, researchers “achieved an ~80 percent success rate while using the fake fingerprints, where the sensors were bypassed at least once.”

To be fair, Apple is improving Touch ID with each new revision of the technology. But, as the security researchers who got past Touch ID with 3D printed fingerprints said, “if the user is a potential target for funded attackers or their device contains sensitive information, we recommend relying more on strong passwords and token two-factor authentication.”

The “drunk in a bar” scenario, Touch ID edition

Another weakness of Touch ID is that if the owner is asleep or unconscious, or sufficiently intoxicated, another person could touch the owner’s finger to the Touch ID sensor to unlock the device.

The verdict on Touch ID

Touch ID score: 8/10

Caveats:

- a highly skilled attacker could theoretically obtain your thumbprint/fingerprint and create a synthetic print that works with Touch ID

- your fingerprint could be lifted from a flat surface you’ve touched, or may be found in a database, notary record, etc., or even a high-resolution photograph of your hand where your prints are visible

- law enforcement or a thief may compel you to put your finger on your Touch ID sensor to unlock it

- if you’re asleep, unconscious, or intoxicated, someone could put your finger on your Touch ID sensor to unlock it

- a thief could force you to unlock your device with threats of violence

- insufficient protection if you have a well-funded or well-connected adversary (e.g. a nation state)

How secure is Optic ID in Apple Vision Pro?

We should mention that there’s one more biometric “ID” authentication method on Apple products: Optic ID. It’s not available on Apple’s iPhone, iPad, or Mac product lines, though.

Optic ID is the biometric authentication technology used exclusively on the Apple Vision Pro. It expands on the concepts behind Touch ID and Face ID, and has a similar false-positive rate. Apple says that, “The probability that a random person in the population could unlock your Apple Vision Pro using Optic ID is less than 1 in 1,000,000.” Of course, if the user has set up only one eye for Optic ID (for accessibility reasons), the probability of a false positive is significantly higher.

Irises as identification

Your eyes’ irises are the physical characteristic that Optic ID uses to identify you. “Optic ID matches against detailed iris structure in the near-infrared domain, which reveals highly unique patterns independent of iris pigmentation.” And, “Optic ID provides intuitive and secure authentication that uses the uniqueness of your iris, made possible by Apple Vision Pro’s high-performance eye-tracking system of LEDs and infrared cameras.”

As with Touch ID, twins and siblings have no advantage, since each individual’s irises are unique, like fingerprints.

Attention awareness with Optic ID

Like Face ID, Optic ID also incorporates attention awareness. The cameras in the Vision Pro constantly track the user’s eyes to see where you’re looking. Authorizations, such as for payments with Apple Pay, are only granted when a user is looking at the app in question.

Arguably more secure, but not a direct competitor

Given that Vision Pro is only usable while in place on an authenticated user’s head, and does not allow anyone else to see what you’re seeing (by default, anyway), Optic ID is less susceptible to side-channel attacks than Touch ID and Face ID. Attack scenarios such as shoulder surfing, forcing someone’s finger onto a sensor, or holding up the device to the owner’s face without warning, are not applicable.

These considerations arguably make Optic ID more secure than Face ID, in spite of both technologies purportedly having the same false-positive rate.

Thus, we can confidently give Optic ID the highest score of all of Apple’s biometric authentication methods. Its security does not have any significant caveats that are known at this time.

The verdict on Optic ID

Optic ID score: 10/10

Caveats:

- enrolling only a single eye (for accessibility) increases the false-positive rate

- only available on Apple Vision Pro; not an option on other Apple products

Other Face ID and Touch ID considerations

With Touch ID, it’s possible to enroll up to five fingerprints, and these could potentially include the prints of additional people. This can be convenient if you want someone you fully trust to always have access to your device without your explicit consent each time. But keep in mind that the more prints you enroll, the less secure your device is, statistically speaking (although it’s still extremely unlikely that a random person touching your Touch ID sensor will get a false positive authentication).

Similarly, with Face ID, it’s possible to add an alternate appearance, which can potentially include a second person. In both scenarios, your device will treat that additional person as though they are you. They can log into your device, buy apps from the App Store or make in-app purchases, make other purchases using Apple Pay, and log into other apps that rely on Face/Touch ID authentication (including password managers and financial account management apps).

The law vs. personal security and privacy

It’s worth pointing out that police, government agents, or customs officials could force you to unlock your device using Face ID or Touch ID. They can simply hold the phone in front of your face, or place your finger on the Touch ID sensor. Thieves could do the same, by threat of violence.

There may also be legal differences between biometric authentication (e.g. Face ID or Touch ID) and a passcode. In some jurisdictions, you could be legally compelled to biometrically unlock a device. If you’re a U.S. citizen, you may be able to plead your Fifth Amendment right to avoid self-incrimination if asked to enter your passcode since it’s something you know—but the same Fifth-Amendment protection may not be universally applicable to biometrics. In the event that these considerations seem concerning to you, it may be more secure to disable Face ID or Touch ID and use only a strong alphanumeric passcode (see the next section on passcode security).

How to quickly, temporarily disable Face ID or Touch ID

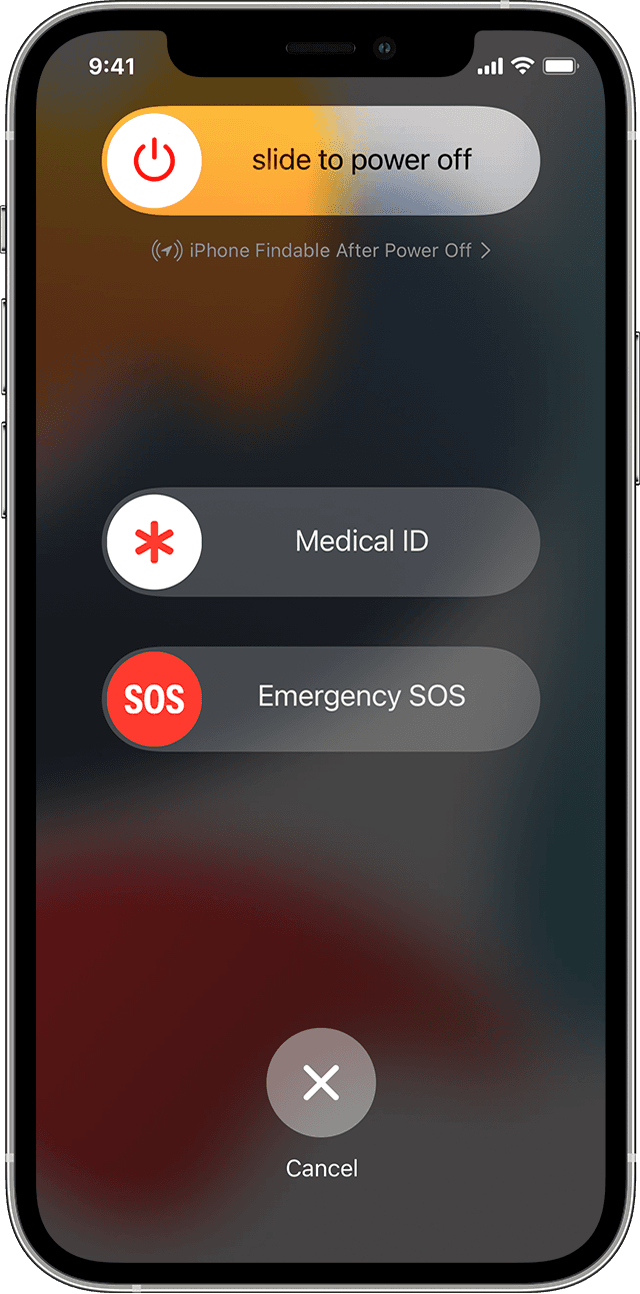

If you think someone is going to force you to unlock your device, and you want to quickly disable Face ID or Touch ID, press and hold the power button and either of the volume buttons for two seconds. The device will go to the Power Off / Emergency screen. Either tap Cancel, or press the power button again, to dismiss that screen. The next time you try to access the phone, you’ll need to enter your passcode. (On some older iPhone models, you may instead need to press the power button several times in rapid succession to disable Touch ID—but beware that on some iPhones, this may also call emergency services after a short countdown. Test these methods when you aren’t under duress to learn which one works with your iPhone.)

Even if you are using Face ID or Touch ID, you should create a complex passcode, because that’s used to access your device when you restart it, and at various other times. In other words, you need a passcode, whereas Face ID and Touch ID are optional technologies that fall back to a passcode when they fail to authenticate or under other circumstances.

How secure is a passcode?

The passcode is the simplest way of protecting mobile devices, and generally involves a string of digits. Early iPhones didn’t require a passcode, and the suggested length of the passcode was four digits. With the release of iOS 9 in 2015, the default increased to six digits.

The theoretical probability of someone randomly guessing a four-digit passcode on the first try is 1 in 10,000. For a six-digit passcode, it is 1 in 1,000,000. In theory, this makes a six-digit passcode roughly as secure as Face ID—but there are other considerations. Both iPhones and iPads limit the number of failed passcode attempts, so manual brute-force attacks don’t work on these devices. However, automated brute-force attacks are possible if the attacker has specialized tools.

Elite password-cracking tools exist

An American company, Grayshift, famously sells an iPhone hacking tool called GrayKey to law enforcement and government agencies. These tools could fall into the wrong hands, although the company does try to prevent unauthorized use. An Israeli company, Cellebrite, works with law enforcement and government agencies, too, but also sells its products to corporate customers. Unauthorized third-party sellers sometimes re-sell Cellebrite tools online, so it’s not at all inconceivable that criminals may own them.

A Grayshift GrayKey device circa 2018. Photo credit: Thomas Reed

Shoulder surfing and password guessing attacks

But even if your adversary doesn’t have access to elite hacking tools, passcodes can potentially be read over someone’s shoulder. In one case, a user’s iPhone was stolen, and the thieves managed to take $30,000 from his bank account, because they knew the passcode and were able to reset other passwords.

In addition, people tend to use highly memorable numbers for passcodes: six digits correspond easily to dates, so by researching someone’s family history—e.g. a wedding date, children’s birthdays, etc.—there’s a good chance that someone can guess the right passcode.

Longer passcodes are more secure

However, lengthen the passcode by a few digits, and it’s much more complicated to guess. For example, a ten-digit passcode with four digits followed by a date would be substantially harder to guess. (Also, that passcode would have 10,000,000,000 possibilities.) When you create a passcode longer than six digits, the iPhone or iPad doesn’t show bullets indicating the length of the passcode. This is good, because it adds more potential complexity, and gives no clues as to the number of digits the passcode contains. A passcode with a variable and unknown length is much harder for brute-force tools to crack.

Adding complexity further enhances long passwords

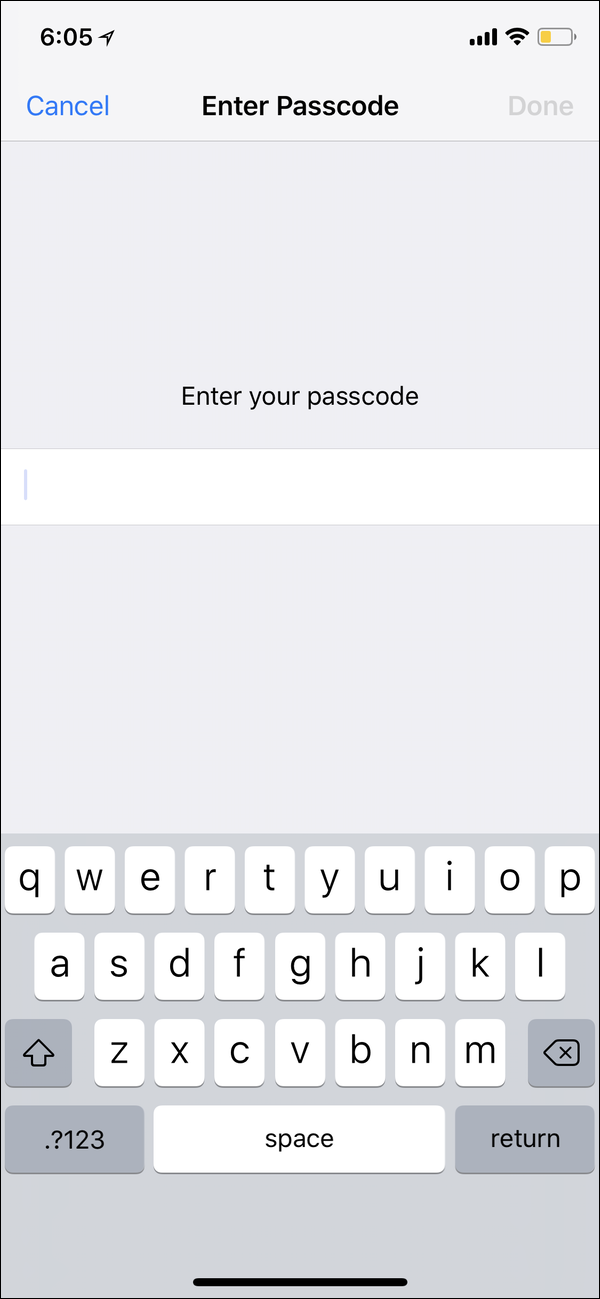

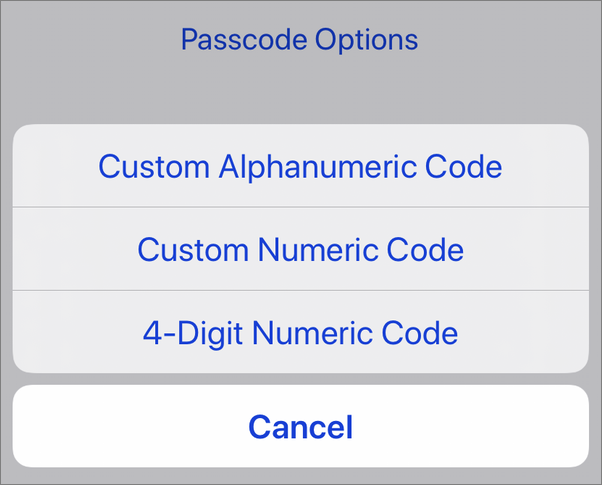

Why not go further and create an alphanumeric passcode? Instead of showing bullets or an empty field with a number pad, the device shows the full keyboard, as above. Anyone attempting to access your device will have no clue how long the passcode is, or whether you are using letters, numbers, our both. In fact, you could even set, say, a six-digit passcode as an alphanumeric passcode. It’s not the most secure, but anyone trying to hack your device won’t know that you’ve only used digits. But there is still the risk of shoulder-surfing: someone watching or filming you as you enter the code.

Passcodes on iPhone and iPad default to 6 digits, but you can choose a custom-length numeric or alphanumeric code instead.

The verdict on passcodes

Passcode scores, and caveats:

- 5/10 for a four-digit passcode

- maximum of 10,000 possibilities, but most people use guessable numbers—e.g. a home address, a partial date in MMDD or DDMM format, the last four digits of a loved one’s phone number, a commonly used PIN like 5683 (the digits for LOVE on a phone’s dial pad), or a PIN that they reuse everywhere and may be found in a data breach or via a phishing attack

- very easy for an attacker to discover your passcode through shoulder surfing

- extremely easy and fast to crack with tools widely available to law enforcement and government agencies

- 7/10 for a six-digit passcode

- maximum of 1,000,000 possibilities, but most people use guessable numbers (most commonly, a date of significance such as an anniversary or birthdate in the MMDDYY or DDMMYY format)

- somewhat easy for an attacker to discover your passcode through shoulder surfing

- easy to crack with tools widely available to law enforcement and government agencies

- 9/10 for a custom, all-digit passcode, of seven or more digits

- a 10-digit passcode, for example, could take up to 10,000,000,000 guesses

- avoid using a telephone number or other easily guessable sequence of numbers

- even more difficult for an attacker to discover your passcode through shoulder surfing

- more difficult for advanced tools to crack via brute force, but not as difficult to crack as an alphanumeric passcode

- 10/10 for a custom, alphanumeric passcode with special characters

- for maximum security, use a unique password (one you don’t use anywhere else; it might end up in a data breach or get phished)

- a sufficiently long and complex password is the most difficult for law enforcement and government agencies’ tools to brute-force crack

- the biggest risk is that you may be more likely to forget a complex password

- a thief could force you to enter your passcode with threats of violence

- even a long, complex password might not protect you from a well-funded or well-connected adversary (e.g. a nation state)

If Hackers Crack a Six-Digit iPhone Passcode, They Can Get All Your Passwords

Key takeaways

All three authentication methods are secure enough for average users. However, the possibility of a lookalike relative getting past your iPhone’s Face ID may concern those with rocky familial relationships. And it’s probably best for almost everyone to avoid using a four-digit passcode.

If you may be a potential target for nation-state hacks, police or government agencies, or thieves, you’ll probably want to choose a custom alphanumeric passcode with special characters. In some cases, you might even consider disabling Face ID or Touch ID and sticking with just a passcode.

Given the risk factors, we’ve chosen to rate the security of the various authentication methods as follows:

- 8/10 for Touch ID

- 9/10 for Face ID

- 10/10 for Optic ID

- 5/10 for a 4-digit passcode

- 7/10 for a 6-digit passcode

- 9/10 for a numeric passcode of 7+ digits

- 10/10 for a unique, alphanumeric password with special characters

All authentication methods have risks. Ultimately, it’s up to each user to choose whether to use Touch/Face ID or to stick with just a passcode. Only you can determine the right balance between security and convenience that best meets your personal needs.

How can I learn more?

Each week on the Intego Mac Podcast, Intego’s Mac security experts discuss the latest Apple news, including security and privacy stories, and offer practical advice on getting the most out of your Apple devices. Be sure to follow the podcast to make sure you don’t miss any episodes.

Each week on the Intego Mac Podcast, Intego’s Mac security experts discuss the latest Apple news, including security and privacy stories, and offer practical advice on getting the most out of your Apple devices. Be sure to follow the podcast to make sure you don’t miss any episodes.

Kirk and Josh did a deep-dive discussion of this topic on episode 254 of the Intego Mac Podcast.

You can also subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and keep an eye here on The Mac Security Blog for the latest Apple security and privacy news. And don’t forget to follow Intego on your favorite social media channels: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()