OSX/Linker: New Mac malware attempts zero-day Gatekeeper bypass

Posted on

by

Joshua Long

Last week, Intego researchers discovered new Mac malware, OSX/Linker, that attempts to leverage a recently disclosed zero-day flaw in macOS’ Gatekeeper protection.

Last week, Intego researchers discovered new Mac malware, OSX/Linker, that attempts to leverage a recently disclosed zero-day flaw in macOS’ Gatekeeper protection.

Let’s examine what we know about this latest Mac malware campaign.

What is the back story?

Before digging into the OSX/Linker malware, it would be helpful, for context, to discuss the “MacOS X GateKeeper Bypass” vulnerability that was publicly disclosed by Filippo Cavallarin on May 24. Gatekeeper is a technology included in macOS that is supposed to check apps downloaded from the Internet for either a revoked developer signature, or for certain specific malware that Apple chooses to detect, before allowing an app to run.

Before digging into the OSX/Linker malware, it would be helpful, for context, to discuss the “MacOS X GateKeeper Bypass” vulnerability that was publicly disclosed by Filippo Cavallarin on May 24. Gatekeeper is a technology included in macOS that is supposed to check apps downloaded from the Internet for either a revoked developer signature, or for certain specific malware that Apple chooses to detect, before allowing an app to run.

The more technical explanation: Cavallarin noted that macOS treats apps loaded from a network share differently than apps downloaded from the Internet. By creating a symbolic link (or “symlink”—similar to an alias) to an app hosted on an attacker-controlled Network File System (NFS) server, and then creating a .zip archive containing that symlink and getting a victim to download it, the app would not be checked by Apple’s rudimentary XProtect bad-download blocker.

The simpler explanation: This trick makes it easier for malware to infect a Mac—even if Apple has a built-in signature that’s supposed to protect your Mac from that malware.

Cavallarin demonstrates the Gatekeeper bypass

Cavallarin says that he reported the vulnerability to Apple on February 22, and Apple told him that the issue would be fixed within 90 days—but Apple missed its deadline, and Cavallarin believed that Apple was no longer responding to his e-mails, so he released his findings publicly via his blog.

What is OSX/Linker?

Early last week, Intego’s malware research team discovered the first known attempts to leverage Cavallarin’s vulnerability, which seem to have been used—at least at first—as a test in preparation for distributing malware.

![]() Although Cavallarin’s vulnerability disclosure specifies a .zip compressed archive, the samples analyzed by Intego were actually disk image files. It seems that malware makers were experimenting to see whether Cavallarin’s vulnerability would work with disk images, too.

Although Cavallarin’s vulnerability disclosure specifies a .zip compressed archive, the samples analyzed by Intego were actually disk image files. It seems that malware makers were experimenting to see whether Cavallarin’s vulnerability would work with disk images, too.

The disk image files were either an ISO 9660 image with a .dmg file name, or an actual Apple Disk Image format .dmg file, depending on the sample. Normally, an ISO image has a .iso or .cdr file name extension, but .dmg (Apple Disk Image) files are much more commonly used to distribute Mac software. (Incidentally, several other Mac malware samples have recently been using the ISO format, possibly in a weak attempt to avoid detection by anti-malware software.)

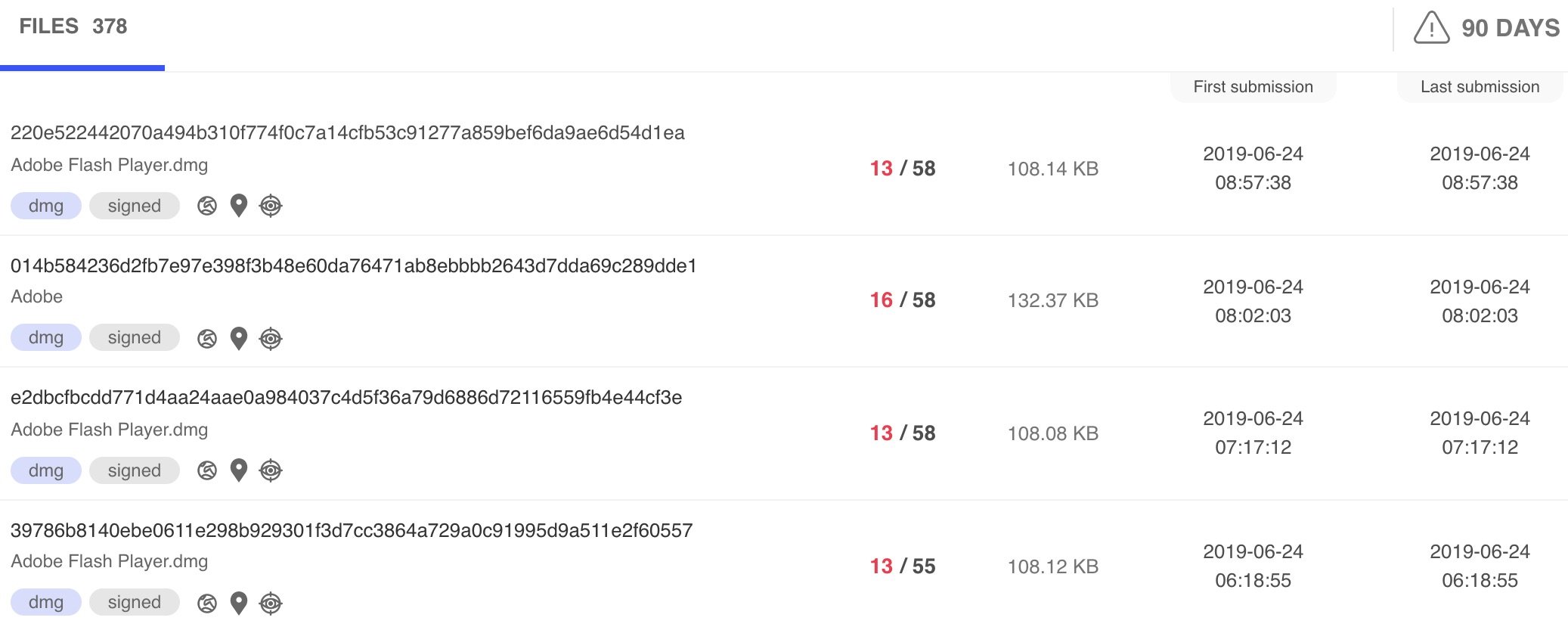

Intego observed four samples that were uploaded to VirusTotal on June 6, seemingly within hours of the creation of each disk image, that all linked to one particular application on an Internet-accessible NFS server.

Who created OSX/Linker disk images?

Each of the four files was uploaded anonymously, meaning the user was not signed into a VirusTotal account.

The first file was uploaded by someone who was either located in Israel, or who was masking their IP address to appear to be in Israel.

The next three samples—the first of which was uploaded just seven minutes after the sample from Israel—were uploaded by a single anonymous user who appeared to be in the United States. Since each successive file was uploaded a short time after each previous one, it seems reasonable to speculate that all four files may have been uploaded by the same person, who forgot to mask his or her IP address until after uploading the first sample.

Because one of the files was signed with an Apple Developer ID (as explained below), it is evident that the OSX/Linker disk images are the handiwork of the developers of the OSX/Surfbuyer adware.

As for the NFS server, its IP address (see the “Indicators of compromise” section below) is owned by Softlayer, now part of IBM Cloud. It seems that the app that was hosted there has been taken down, but it’s unclear whether it was removed voluntarily or was removed by the hosting company. However, while it is not clear whether the same person who uploaded the app may still have control over the NFS server, fragments of related files do still exist on the server.

Was this malware “in the wild”?

By the time the disk images had been discovered and analyzed, the NFS server was no longer hosting the Mac app referenced by the disk images’ symlinks. It is not clear whether any of these specific disk images were ever part of an in-the-wild malware campaign. It is possible that these disk images, or subsequent disk images, may have been used in small-scale or targeted attacks, but so far this remains unknown.

Given that the NFS server was no longer hosting an app at the time the disk images were analyzed, this means that a sample of the app itself could not be obtained for analysis. So how can one be certain that the app was malicious? There are a number of clear indicators of foul play. The disk images are disguised as Adobe Flash Player installers, which is one of the most common ways malware creators trick Mac users into installing malware. The fourth OSX/Linker disk image is code-signed by an Apple Developer ID—Mastura Fenny (2PVD64XRF3)—that has been used to sign literally hundreds of fake Flash Player files over the past 90 days, associated with the OSX/Surfbuyer adware family.

Hundreds of fake Flash files have been signed by “Mastura Fenny.”

Intego reported the Developer ID to Apple, and at the time of publication Apple was in the process of revoking the developer’s certificate.

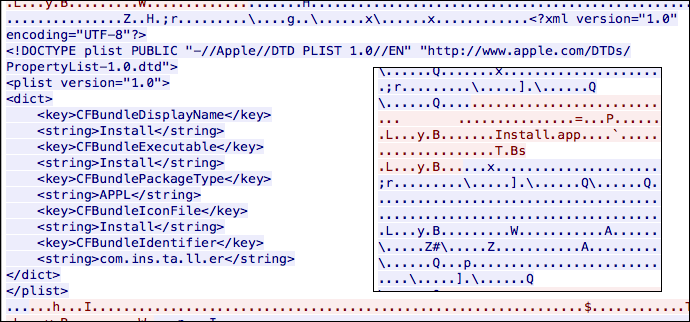

Update: Threat researcher Adam Thomas observed that VirusTotal’s behavioral analysis of two OSX/Linker samples included PCAP (network packet capture) files, from which it is possible to reconstruct the version of the Install.app that was on the NFS server at the time of the analysis. At the time, the app seemed to be a placeholder that did not do much other than create a temporary text file:

#!/bin/bash echo "BAHSS" >> /tmp/out.txt

Reconstructions of an Install.app placeholder. Credit: Thomas

This seems consistent with the theory that the malware maker was merely conducting some detection testing reconnaissance. However, because the .app inside the disk images is dynamically linked, it could change on the server side at any time—without the disk image needing to be modified at all. Thus, it’s possible that the same disk images (or newer versions that were never uploaded to VirusTotal) could later have been used to distribute an app that actually executed malicious code on a victim’s Mac.

An anonymous researcher also pointed out, and Thomas likewise observed, that although an “Installer.app” is no longer on the NFS server, a file called Install.command can currently be found there. If executed, the shell script would similarly just append a string to the same temporary text file:

#!/bin/bash echo "VPNVPN" >> /tmp/out.txt

What should Mac users learn from this?

Mac malware developers are actively experimenting with new ways of bypassing Apple’s built-in protection mechanisms—and attackers are often successful in doing so.

Unfortunately, it’s a myth that Macs are somehow inherently safer than Windows PCs. Within the past month alone, there have been several new Mac malware campaigns aside from OSX/Linker. Therefore, Mac users would be wise to take steps to actively protect themselves from malware threats.

Update: Intego has discovered yet another new variety of Mac malware: OSX/CrescentCore: Mac malware designed to evade antivirus

Is my Mac infected?

Users of Intego VirusBarrier X9 (part of Intego’s Mac Premium Bundle X9 suite) or Flextivity will be notified if a related file is found on their Mac; it will be detected as OSX/Linker.

If you aren’t a VirusBarrier X9 user yet, and if you think your Mac might be infected, you can scan your Mac with VirusBarrier Scanner (available for free on the Mac App Store) to check for any infections. After you scan your Mac, your best bet to prevent future infections is to get VirusBarrier X9, which includes real-time scanning functionality—a critical feature to block malware before it can harm your Mac.

Indicators of compromise

If you’re a systems administrator and want to check for potentially infected Macs on your network, you can check whether any Macs connected to the following IP address over NFS ports (e.g. TCP or UDP ports 111 or 875, or TCP port 2049) between May 24 and June 18:

108.168.175 .167

More broadly, if you know that your users should never need to connect to public-facing NFS servers, you can look for indications of recent connections to any non-private IP address on NFS ports, as a means of potentially finding other variations of the attack.

If you discover a Mac that seems to have connected to that IP address between those dates, or if you believe you’ve found evidence of a similar attack, please contact Intego support so we can work with you to investigate further.

Potential mitigations of Cavallarin’s vulnerability

Network administrators who know that their users will never need to connect to a public NFS server can lock down their network to prevent NFS communications with external IP addresses.

For home users, unfortunately there isn’t a simple solution for preventing this type of attack, until or unless Apple releases a macOS security update to mitigate the vulnerability. Cavallarin describes a possible temporary mitigation (opening /etc/auto_master in a text editor and adding # to the beginning of the line that starts with /net). Modifying system configuration files is something that only experienced and knowledgeable users should consider attempting.

How can I learn more?

We talked about OSX/Linker and other recent malware on episode 88 of the Intego Mac Podcast—be sure to subscribe to make sure you don’t miss any episodes. You’ll also want to subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and keep an eye here on The Mac Security Blog for the latest Apple security and privacy news.

We talked about OSX/Linker and other recent malware on episode 88 of the Intego Mac Podcast—be sure to subscribe to make sure you don’t miss any episodes. You’ll also want to subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and keep an eye here on The Mac Security Blog for the latest Apple security and privacy news.

You can also follow Intego on your favorite social and media channels: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube (click the ? to get notified about new videos).

Image of metal chain with red link by ccPixs.com; CC BY 3.0.