Do OS X’s Built-In Security Features Offer Good Enough Protection?

Posted on

by

Lysa Myers

![]()

There has been a lot of talk about the malware that hit a number of high profile Mac developers and the fact that Pintsized got through OS X’s security features. While Apple’s built-in features are definitely helpful and vastly better than being on the Internet totally unprotected, they are not designed to be a full security solution. There are many very simple ways to get around these security features, and there is no functionality to clean up if something does bypass them.

You may be wondering, “What are these various security functions? How are they helpful? And how can they be circumvented?” Here’s a rundown of Apple’s most high-profile security features.

XProtect and Gatekeeper

XProtect was designed as a way to prevent or mitigate some general problems and specific threats that were hitting a large section of their userbase. The general protections are the warnings you see about potentially dangerous file-types. The anti-malware component does help detect malware, but it’s intended to be strictly reactive. The detections are quite specific, and there is no heuristic or generic detection. There is almost no chance it would detect something brand new.

XProtect is not intended to be what one would consider a “modern AV product” – it’s only designed to find a very small handful of existing threats. There’s also a big window between the time researchers (from Apple or from other security companies) discover new Mac-related threats and when they’re added to XProtect. Malware that is less prevalent never makes it into XProtect, which isn’t much help if you’re one of those few who are affected. In the case of the watering hole attack, XProtect was not updated to cover this threat – Apple created a removal tool which was originally bundled with a Java update, which makes sense in that the threat relied on Java to infect.

Gatekeeper was designed to help limit the applications that you can intentionally install. It can be helpful when a threat relies solely on social engineering to get you to infect your system – the dreaded double-click of doom. But if the malware authors manage to get hold of a certificate to sign their creations so that it looks legit, you’re out of luck. Or if the threat uses an exploit (such as the Java 0-day in this instance) to install silently, you’re once again out of luck.

Both Gatekeeper and XProtect care about where you got a given file – if you’ve gotten a file from fixed media (from a disk, rather than from the Internet) or from applications that are not ones that it monitors, it won’t warn you. And if it’s one of the file-types OS X considers safe, it also will not warn you. And both features only concern themselves with files coming into your machine. They won’t prevent malware from going out (should you share a file via Dropbox or email, for instance).

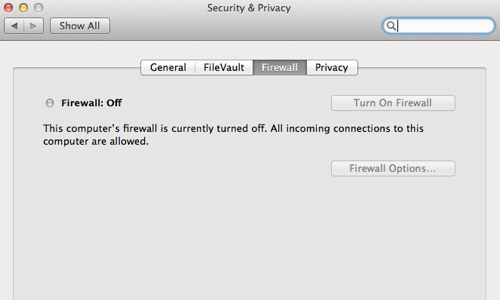

Apple’s Firewall

The Application Firewall was designed to protect you from attacks coming from outside your machine – it filters inbound connections, but not outbound. This is great if someone is trying to use common attack tools that try to look for listening ports, but not so great if the threat has somehow managed to get on your machine already, as in the case of malware. If malware or hackers manage to get into your machine, they can send your data out to attackers. Ideally, you should be alerted to strange traffic both coming into and going out of your machine, so if they manage to bypass one defense, they may not get past the next.

You have three main options when you set up Apple’s firewall:

- The default option is to let only signed applications connect into your computer.

- Another option is to block all non-essential incoming connections, which will obviously limit many common programs that might need to communicate with your machine.

- The final option is to enable “Stealth Mode,” which means it will not acknowledge (or respond to) requests from diagnostic tools that use ICMP, like Ping or Traceroute.

You can use any one option individually or in combination with the others. And you can allow or block specific applications separate from these three options.

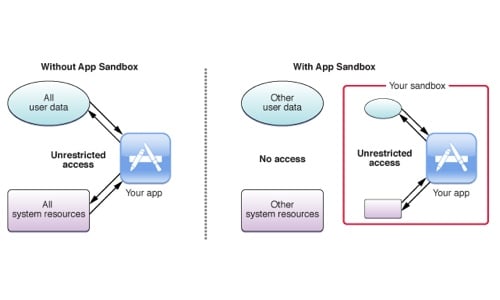

Sandboxing

When you’re dealing with something potentially explosive, sometimes the best thing to do is to try and limit the damage. Exploits work by busting their way out of the context of an application so they can get into areas where they’re not really supposed to be in order to run whatever code they like. So, if an app developer creates a sandboxed version of their product, they can essentially put themselves in a walled-off enclosure that limits what damage a potential exploit can do. Apple has required this of apps that are sold in their App Store. It’s good for users, in a security context, for developers to take this measure if they can. (Plus, being in the App Store is good exposure for the developer.)

As we all know, because iOS only lets you install apps from the App Store (unless you’ve jailbroken your device), this is how all iOS apps operate. This is a big limitation of their functionality versus what you can do with apps on a mobile OS like Android, but also why there has been very little interest by malware authors in creating threats for iOS thus far. It’s simply too much work for too little benefit right now.

Because it severely limits what apps can do, for many products sandboxing may simply degrade the user experience too much. Applications that are popular due to 3rd party plugins, allow you to access files throughout your system or on a network, or interact with non-USB devices can’t be sandboxed. That covers a lot of popular products, including utilities like anti-virus software, among many others. So while it does limit the possibility and power of exploits, it also severely limits the power of the applications themselves, so not all developers can or will sandbox their apps. (Searching for websites pertaining to OS X Sandboxed Apps largely returns articles with words like Sad, Frustration, Ruin, and Killjoy in the title;, and these articles are mostly written by app developers. ‘Nuff said.)

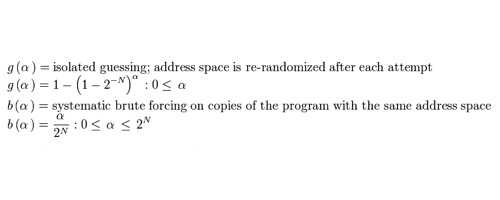

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

Without going into painful technical detail, the short of ASLR is that it tries to make it harder for people to use vulnerabilities in software to create exploits that run arbitrary code. At this point, every major OS has implemented ASLR to some extent, and these versions have been around for many years. Yes, even Windows and Android have ASLR. And, as we’ve not yet heard about the end of exploits, and the jailbreaks or malware that use them, I’m gonna go out on a limb and say this has not really been a sufficient deterrent in the fight against vulnerabilities leading to exploits. Bypassing ASLR has simply become the new cost of entry.

It’s a Start, But It’s Not Foolproof

In all these cases, these security features are awesome tools that make you way safer than having no protection at all. They’re meant to help keep you safe from some fairly common types of attacks, but by no means all types. Each feature leaves some pretty large opportunities for malware to get through. And all OS X users have access to this same protection. That means almost all Mac users are protected to at least this degree, and attackers know this. It’s fairly trivial to go beyond that level, which is exactly what happened to the Mac developers that got hit with Pintsized. To be just a little better protected than the next guy, you need to apply additional tools that cover more advanced types of attacks.

Apple app sandbox image via Mac Developer Library