Did the NightOwl app really join Macs to a botnet army?

Posted on

by

Jay Vrijenhoek and Joshua Long

In late June, a web developer named Taylor Robinson wrote a blog post titled, “Uninstall the Nightowl App, now.”

NightOwl is a third-party app that has been around since 2018. It’s supposed to offer more customizability than Apple’s built-in Night Shift feature in macOS; both can automatically toggle your display to warmer colors after dark.

But Robinson claims that NightOwl has taken a turn toward the dark side. Supposedly, it silently enlists Macs in a botnet army.

Apple seems to agree that something shady is afoot; the company revoked the NightOwl developer’s code-signing certificate, forcing the developer to remove NightOwl’s download link from its site.

So what’s really going on? Let’s break down what we know about NightOwl.

In this article:

- What is NightOwl?

- What events led up to Robinson’s blog post in June?

- Does NightOwl really join Macs to a botnet?

- Why is this suddenly a hot topic in August?

- What does NightOwl’s original developer think about the situation?

- What does NightOwl’s current developer have to say?

- Is NightOwl malware, a PUA, or something else?

- A cautionary tale: good apps can take a turn for the worse

- Should I uninstall NightOwl? How can I do so?

- How can one remove or prevent Mac malware and PUAs?

- Indicators of compromise (IoCs) for affected NightOwl versions

- Do security vendors detect this by any other names?

- How can I learn more?

What is NightOwl?

NightOwl is an app that lets you control the macOS Dark Mode and Light Mode on a much more granular level. You can pick which apps remain Light when the rest of the system goes Dark, and vice versa. You can set it to toggle modes at a certain schedule, or as the sun rises and sets. Moreover, you can toggle between modes with a hotkey. And the cute owl sounds when switching between modes are just icing on the cake.

The utility offered Mac users an extra level of control beyond what’s built into macOS. It has remained popular ever since.

What events led to Robinson’s blog post in June?

NightOwl’s original developer, Benjamin Kramser, says that he was no longer able to personally continue to develop the app due to time constraints. This led him to sell the project to a company called TPE.FYI LLC in November 2022.

It isn’t uncommon for apps to get acquired by a bigger company. Even companies as big as Apple have been known to acquire smaller companies to obtain all the rights to their software.

According to public records, TPE.FYI LLC was formally established as a business entity in September 2018, but was dissolved in March 2023.

The same month that TPE.FYI was supposedly dissolved, the NightOwl website apparently introduced a new Terms and Conditions page. For anyone who may have happened to read it, this page contains some potentially concerning statements, such as:

“WHEREAS, NightOwl app enables Users to share internet traffic by modifying their device’s network settings to be used as a gateway for internet traffic. Additionally, the User’s device acts as a gateway for NightOwl app’s Clients, including companies that specialize in web and market research, SEO, brand protection, content delivery, cybersecurity, etc.”

While such language might stop you from installing an app, this change apparently wasn’t called out very clearly to users. What’s worse, this functionality could neither be opted into nor opted out of; it was simply baked into the product.

Does NightOwl really join Macs to a botnet?

The claim in Taylor Robinson’s blog post that NightOwl “forcibly joins your devices into a botnet” is quite a strong accusation. Let’s examine what that implies, and whether the current version of NightOwl has such capabilities.

What is a botnet?

When a computer or device is part of a botnet, that means software is installed that uses computing resources and Internet bandwidth to carry out tasks on behalf of a botmaster (bot operator). Such tasks may including participating in distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, sending spam, generating fake views or clicks, or other unethical behavior.

Generally, all of this is done without the knowledge or explicit consent of the owner of that device or computer.

A bot (or zombie) is an infected computer or device that is part of a botnet army.

Does NightOwl include bot-like functionality?

According to Robinson, NightOwl was connecting to a remote SSH server, and acted as an HTTP(S) proxy server for the developer. Theoretically, this could mean that the current NightOwl developer could try to leverage users’ devices as part of a botnet to conduct DDoS attacks against Web servers, or generate fake clicks or views.

Robinson also notes that NightOwl contains code related to a service called Pawns (or Pawns.app), which supposedly pays users up to 20 cents per gigabyte for sharing their network bandwidth. Again, this seems to imply that some third party could theoretically leverage NightOwl users’ Internet connections as proxies to send DoS or click fraud traffic.

Notably, Robinson did not claim to have observed NightOwl actually engaging in these types of activities commonly associated with botnets.

Of course, this behavior happens behind the scenes; users of NightOwl will generally have no idea that any of this is happening. Users also wouldn’t get a share of any revenue generated by Pawns traffic; all of the potential profits would go to the current NightOwl developer.

What other behavior does NightOwl engage in?

Robinson goes into further technical detail about how NightOwl uses a LaunchAgent to kick off an AutoUpdate daemon. The daemon runs as root, and it cannot be disabled through the app. Turning off the “Send Statistics” option in the app does not disable the LaunchAgent, either.

Further details include how NightOwl may be making use of several open-source software packages without including the appropriate licenses.

Finally, Robinson explains the Pawns component:

The application also seems to use the Pawns SDK, which is an app offers to pay users $0.20 per GB of their internet shared. This service is operated by IPRoyal, a proxy company that will sell you residential proxy connections for $1.75/GB, and advertises “100% ethically sourced IPs”.

IPRoyal is apparently overconfident, at best, about its “100% ethically sourced IPs” claim. The company boasts of more than 8 million IP addresses. Pawns, for its part, advertises that its clients (evidently including the current NightOwl developer) can get paid up to $2 per month, per unique IP address.

Residential proxy services could get you into trouble with the law

And what precisely could such a “residential proxy” service do? It could route its clients’ Internet traffic through any computer with the software installed.

And why might a client want to pay for such a proxy service? Perhaps to do sketchy things—such as making malicious edits to Wikipedia to spread disinformation, creating social media accounts en masse for fake engagement, or even accessing illegal pornography—all of which appear to originate from your home or workplace.

So, in a worst-case scenario, you could potentially be investigated and arrested for crimes you did not commit, all because of software on your computer that you didn’t even know existed.

Why is this suddenly a hot topic in August?

The recent press coverage about NightOwl typically just links back to Robinson’s blog post from June, offering little additional information. The likely source of the sudden interest is an August 8 post on Y Combinator’s Hacker News. From there, the story seems to have been picked up by several online tech publications.

Due to this new attention, the current NightOwl developer gave a statement to HowToGeek that reads, in part:

“Given some users high level of concern we are working to give users an option to opt out of this. If we are able to re-release the app we will either completely remove this SDK or give an easy option for disabling. We apologize for the inconvenience and concern created.”

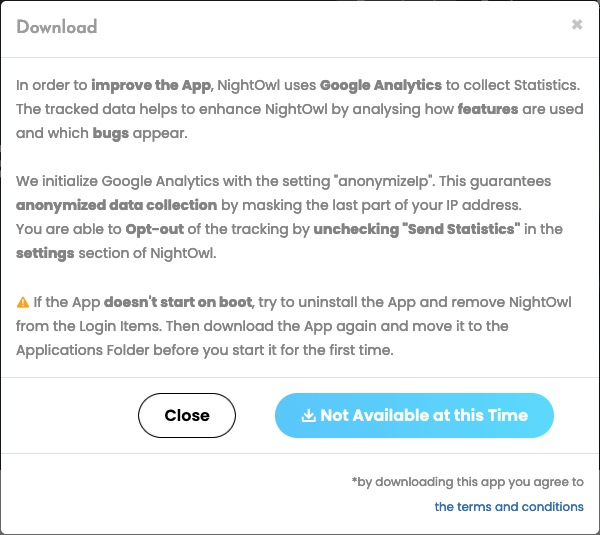

Around this time the download was made unavailable on the NightOwl website.

While an opt-out is a start, this is not the best approach. “Opt in” would be preferable, as the user must manually check a box to enable the functionality. It also isn’t clear from that statement whether the company plans to make the potentially undesirable behavior much more apparent to end users, with notifications upon installation or upgrade.

The desire to somehow make money from NightOwl or any app makes sense, but it’s important to do so in a fully transparent and ethical way. At the time the company acquired NightOwl, TPE.FYI LLC communicated to the original developer that it would use normal, ethical methods of monetizing the app, namely a subscription model with more advanced features.

What does NightOwl’s original developer think about the situation?

NightOwl’s original developer, Benjamin Kramser, makes the following statement on his site:

“Nightowl got acquired by TPE.FYI LLC in November 2022

“Due to time constraints, I could no longer personally continue the development of NightOwl. Therefore, in November 2022, I made the decision to sell my beloved tool to ‘TPE.FYI LLC’. This decision was made with the understanding that new (Pro) features and a subscription model would be introduced. Unfortunately, ‘TPE.FYI LLC’ has opted to monetize the app by integrating a third-party SDK. This decision is not affiliated with me in any way, and I do not endorse it in any form.”

We reached out to Kramser with follow-up questions, and he responded:

“I regret the current situation surrounding NightOwl.

“There’s not much I can add to what has already been communicated on my website. I can only supplement that TPE.FYI didn’t approach me [to buy NightOwl] actively on their own initiative. As described on the website, due to time constraints, I was actively searching for a developer/company to continue the project and provide users with new features.”

Unfortunately, the company that acquired NightOwl appears to have not stayed true to its word about how it would monetize the app; either that, or perhaps another developer took over the project after TPE.FYI was reportedly dissolved.

What does NightOwl’s current developer have to say?

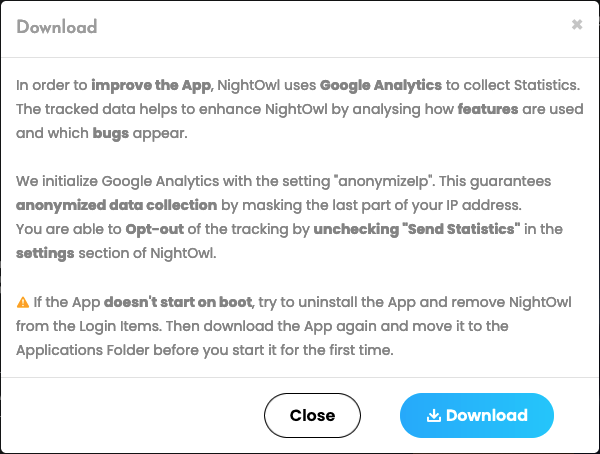

The current NightOwl developer has updated the nightowlapp.co site with a pop-up message stating the following:

“We want to address recent claims that NightOwl contains malware. We want to assure you that these claims are inaccurate and false. Our app does not contain any form of malware. The concerns raised are based on a mistaken identification, and we are actively working with all major antivirus companies to rectify this situation promptly.

“Your security and trust are of utmost importance to us. We kindly ask for your patience as we address this matter with the necessary parties. Thank you for your understanding.”

We reached out via e-mail with follow-up questions. In a reply to Intego, NightOwl’s current developer added:

“It is of crucial importance to us that our users feel comfortable and informed about the usage of NightOwl.

“We have partnered with a highly reputable residential proxy service to monetize NightOwl. We added their SDK to the backend of the app that allows our partner’s users to send some requests through the NightOwl user’s IP address. It’s important to note that we solely collect users’ IP addresses. No other user data is collected. We have disclosed this in our terms and conditions.

“We understand that some users have expressed concerns about this, and we apologize for any inconvenience or worry this situation may have caused. In response to this feedback, we are actively working to provide users with an option to opt out. Should we have the opportunity to re-release the app, we are committed to implementing a straightforward method for users to disable this feature.

“Our team is dedicated to resolving this matter swiftly and effectively, ensuring that NightOwl can once again be enjoyed by users without any reservations. We greatly value the trust our users place in us and want to assure them that their satisfaction, security, and privacy remain our utmost priorities.”

The developer disputes some of Robinson’s claims

When asked whether they disputed any of the claims in Robinson’s blog post, the company stated:

“Yes, we dispute the claims made in the post regarding (a) that this blogger contacted us for comment, they did not. If concerns had been raised directly we would have happily addressed and them. (b) that this is a botnet or in some way malicious. It is not malicious. We made some mistakes in the implementation that we have been working to resolve for several weeks already.”

The developer’s plans moving forward

Intego also asked whether the developer intends to re-release NightOwl under a different developer ID, since Apple appears to have blocked the previous account. The company responded:

“Our dev team has made several changes related to the concerns in this blog post and are taking the feedback we are receiving from ESET, Microsoft, etc. We hope that we can solve these issues with the antivirus companies and with our Apple Developer account and push an update that solves these problems. If we are not able to we will likely shut down NightOwl or we will sell it.”

This seems to imply that, at least for the time being, the company does not plan to attempt to obtain a second Apple developer account under which to re-release the app—at least not without first making changes to try to comply with Apple’s terms of service. Perhaps the company might change its approach if it’s unable to return to Apple’s good graces.

When asked whether the company plans to continue using tinyproxy, Pawns, or similar frameworks or monetizable behavior in NightOwl, the company responded, “If we are able to distribute the NightOwl app again we will look at all legitimate monetization options that are available.” Presumably, this may include continuing to use Pawns, since the company considers it “highly reputable.”

Will monetization functionality be opt-in, or opt-out?

The developer had stated earlier that “we are actively working to provide users with an option to opt out.” We sought further clarification. Was their intention to change the monetization functionality to an opt-in or opt-out model going forward?

They stated, “If we are able to distribute the app again we will definitely make this feature optional and clear as to what it does.”

This sounds like an improvement, but doesn’t clearly indicate the developer’s intentions. It’s unclear from this statement whether users will have to opt in to enable monetization features, or whether the functionality will remain enabled by default, requiring users to take action to opt out.

Additional Q&A with the current NightOwl developer

We also asked several other follow-up questions. Here are our questions and their responses:

Q. How do you plan to earn back the trust of NightOwl users?

A. We will add more clarity around our monetization practices.

Q. Will you rectify the alleged GPL violation over the use of tinyproxy?

A. Yes, definitely. That has already been addressed if we were allowed to push an update.

Q. What have you learned from this experience? How will your company’s business practices change going forward?

A. We have taken several painful lessons from this experience that we will use to try and improve our practices and communication with our customers.

In a later e-mail, we also asked whether TPE.FYI LLC is the current owner of NightOwl. We noted that the company name is nowhere to be found on the nightowlapp.co Web site, and public records seem to indicate that the company was dissolved around the same time that the new monetization behavior appears to have been implemented. As of publication time, the current developer had not responded to this inquiry.

Oddly, the current developer’s site continues to strongly imply that Kramser is still developing NightOwl. The app’s homepage contains the original developer’s story, “Why I developed NightOwl,” without offering any indication that Kramser is no longer involved with the project.

Is NightOwl malware, a PUA, or something else?

So is NightOwl malware or not? In our brief testing, we have not observed direct evidence that the software itself is overtly malicious or directly dangerous to users, so it does not appear to meet the strictest definition of harmful malware.

However, broader definitions of malware can include software with behavior that some users would find undesirable, objectionable, deceptive, or a violation of trust.

The current version of NightOwl does properly fall under the category of “potentially unwanted apps” (PUA, also known as “potentially unwanted programs” or PUP). This is specifically because of the unrelated background functionality of NightOwl that has nothing to do with its stated purpose, and which isn’t perfectly transparent to users.

The app should have informed users—either upon upgrading from a version by the original developer, or upon initial installation—that the app contained functionality designed to earn revenue for the current developer by utilizing the user’s computer and Internet connection. Ideally, this would have been presented to the user in an explanatory dialog box, with the functionality disabled by default, requiring the user to click a checkbox to “opt in” to monetarily support the developer.

If the developer really wanted some kind of payment from its users, another alternative could have been to switch the app to a paid model, or a “freemium” model that offered additional features with a paid upgrade.

Defaulting to behavior such as Internet connectivity sharing, cryptocurrency mining, injecting ads, or similar—without verifying that the user understands the implications and can change their mind later—is arguably a less-than-ethical practice. Such behavior often leads to security products detecting an app or some of its components as “potentially unwanted,” as was the case with NightOwl.

A cautionary tale: good apps can take a turn for the worse

In this case, NightOwl—a popular and perfectly legitimate app—changed ownership, after which a new owner introduced potentially unwanted changes the end-user was likely not aware of. The app updated and continued to work, so why would users go looking for updated terms of service?

You might recall that back in 2016, a threat actor replaced a legitimate BitTorrent client, Transmission, with a modified version on the company’s official servers. Users who updated the app during that time wound up with their Macs infected with malware. Five months later, the same thing happened again; the same legitimate app was compromised by a threat actor twice in the same year.

The stories of NightOwl and Transmission are very different in terms of both who was responsible for the apps’ changes and the level of potential harm imposed by those changes. However, both stories are similar in that users downloaded an app that was supposed to be safe based on past experience, but it turned out to have been modified with unexpected and undesirable functionality.

In May of this year, we reported on the Intego Mac Podcast that nearly three dozen browser extensions in the Chrome Web Store contained search-hijacking code. Some of the extensions had contained that unadvertised malicious functionality for nearly two years before Wladimir Palant blogged about the problem, and Google finally took them down. But in the mean time, those 34 extensions had amassed 87 million users.

Intego’s Chief Security Analyst, Josh Long, pointed out on the podcast that sometimes this sort of thing happens “when a developer stops working on an extension or app, [and] someone else comes along and offers the developer a bunch of money and says, ‘Here, I’ll take over development.’ And then they start developing it and add malicious things to it.” While it’s unclear whether that may have been the case with the 34 Chrome extensions, it has certainly happened before, and will inevitably happen again—quite possibly with other Mac apps.

In fact, just days ago, the developer of a Chrome extension with 300,000 users spoke out about having received more than 130 solicitations to “monetize” his extension. If cybercriminals can find a way to infect or exploit hundreds of thousands of users at once, wouldn’t you expect them to at least try? And wouldn’t you expect that some developer, at some point, will take the bait, perhaps not fully understanding what they’re getting into? This is a serious problem, and it’s not going away anytime soon.

Stay vigilant; read EULAs, and use protection software

In short, there are many ways that software with potentially unwanted behavior can find its way onto your Mac.

Unless an app makes its terms of use very clear—and makes it obvious whenever there are changes—users will likely not notice. With almost every app, service, and website you use, you must agree to terms of use (TOU) or end-user license agreements (EULA). Sometimes these can change overnight, without any fanfare—though often you’ll get an e-mail or a pop-up in your app to notify you that something has changed.

The reality is that very few people actually read (and understand) all of the terms of use before clicking or tapping “Accept.” If we did, we’d all use a lot fewer apps and services, as most of them contain clauses with which we would not be comfortable.

Back in 2019, we discussed on the Intego Mac Podcast a New York Times exposé. In it, the Times claimed that privacy policies (which are full of legalese, much like TOUs and EULAs) “were an incomprehensible disaster.” In fact, “Only Immanuel Kant’s famously difficult ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ registers a more challenging readability score than Facebook’s privacy policy,” according to the piece’s author.

But even if you can’t fully comprehend legalese, it’s a good idea to at least try to understand what you’re getting into. At least skim through the text to see if any key words stand out. Even if you do decide to hit that “Accept” button, at least you’ll have a somewhat better idea of potential privacy or security implications.

As additional layers of protection, Intego VirusBarrier can watch for malware and PUAs for you, and Intego NetBarrier can alert you if suspicious connections are attempted by any app or background process. Both tools are available as part of Intego’s Mac Internet Security X9 and full-featured Mac Premium Bundle X9 software suites.

Should I uninstall NightOwl? How can I do so?

Although NightOwl is not overtly malicious, the app does contain background monetization functionality that cannot be opted out of within the app itself. Some third-party sites that have mentioned NightOwl in the past have either removed their articles or added warning text, citing concerns.

Until the app introduces a way to opt out, and provides clear notices during installation and upon launching the app, some users may wish to uninstall it. Some of NightOwl’s functionality is built into macOS, so removing it will not be a devastating loss to most users.

If you currently have NightOwl installed and want to manually uninstall it, you can run the following commands in the Terminal app. (These commands are a modified version of Robinson’s manual removal instructions.) Note that there is no need to run these commands if you’ve never used NightOwl on your Mac, or if you uninstalled it before October 2022. Always be careful when running Terminal commands.

- First, you’ll ensure that NightOwl isn’t running for anyone who’s currently logged into your Mac. Copy and paste (or type) the following into Terminal, and press the Enter key on the keyboard.

sudo killall NightOwlYou’ll be prompted to enter your password. Type it and press Enter. - Next, you’ll unload NightOwl’s LaunchAgent (its method of persistence). Copy and paste the following into Terminal, and press the Enter key on the keyboard.

launchctl unload ~/Library/LaunchAgents/NightOwlUpdater.plist - Third, you’ll verify whether NightOwl’s AutoUpdate app is running, and if so, you’ll quit it. Copy and paste this entire command into Terminal, then press Enter.

sudo ps -ax | grep /Applications/NightOwl.app/Contents/Helpers/AutoUpdate | grep -v grepIf you’re immediately taken back to the%prompt, then the AutoUpdate app isn’t running, and you can move on to step 4. If, however, you get a line that starts with a number, for example…#### ?? 0:01.09 /Applications/NightOwl.app/Contents/Helpers/AutoUpdate

…that means the app is running, so you’ll need to type the following into the Terminal (replacing “####” with the unique number for your system) and press Enter.

sudo kill -9 #### - Next, you’ll remove the app from your Applications folder. You can either drag it to the Trash, or copy and paste the following command into Terminal and press Enter.

sudo rm -rf /Applications/NightOwl.app - Finally, you’ll uninstall the LaunchAgent. Since the LaunchAgent file is installed on a per-user basis, the following command should remove any copies from all user accounts on your Mac. Copy and paste this entire command into Terminal, then press Enter.

sudo zsh -c "rm /Users/*/Library/LaunchAgents/NightOwlUpdater.plist"

Again, it’s only necessary to run these commands if you currently have NightOwl installed and wish to remove it from your Mac.

How can one remove or prevent Mac malware and PUAs?

Intego VirusBarrier X9, included with Intego’s Mac Premium Bundle X9, can protect against, detect, and eliminate potentially unwanted components of NightOwl. Intego products detect components of applicable versions of NightOwl as variants of OSX/Agent or OSX/Downloader.go.

VirusBarrier had already been detecting many components related to NightOwl’s potentially unwanted background behavior for months before this story hit the news. Additionally, Intego NetBarrier would have warned users about NightOwl’s attempts to connect to the developer’s sketchy-sounding “squidyproxy” servers.

If you believe your Mac may have a PUA or may be infected with malware—or to prevent future infections—use trusted endpoint protection software. VirusBarrier is an award-winning antivirus, designed by Mac security experts, that includes real-time protection. It’s compatible with a variety of Mac hardware and OS versions, including the latest Apple silicon Macs running macOS Ventura.

Additionally, if you use a Windows PC, Intego Antivirus for Windows can keep your computer protected from malware.

VirusBarrier X6, X7, and X8 on older Mac OS X versions also provide protection. Note, however, that it is best to upgrade to the latest versions of macOS and VirusBarrier; this will help ensure your Mac gets all the latest security updates from Apple.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs) for affected NightOwl versions

The following SHA-256 hashes relate to components of affected versions of NightOwl:

0f6413100fbdc43bf4a8a044f3d1a9bb5394d04eb2f2006a5337d640eb668176 0f709d2ddd851cd97faa9e873d9a733fa125b5f2c0d90448bf48b1e00558f33b 0fc3cc3c6557c12551adfec80e68cd16605fa2c306e792dc2a3e6e50b7389e37 14d1da4c833f3171c7d1a15c680673438ec899da1f524e8b1389c42e209412df 22d3b5e8dbaaa0956ff18580f3298fbe7a2e93c22714b8a47a810052e544e20d 266f3dd7a0c27b0730e9a893cde59ede22e49aa6c93d5e3b1fbba1436f3336ee 2e32ca66934d2395d4b05a5d91408f3fc9d633e0fa2a4b6ec27e5d9ccbd1c558 2e9baf82d33185d6c26b839dc27c9de3fcbb6e26831288c2b5233a66c7b9127a 34fd2f6671fb633aa91547abb5c169aeace49ad5150df1dba52a09f6bc09b25f 375ef0eb310d3fa82ddb5357ecd35e6991cfd0540635616ffc799bf9c6fe8816 3d4c278b1f19aa5a57ab12a6ccb4f9fa6039ee77c6c292ce541a252a99769404 3fae06e5604a30725c1076a80c89d944570603781c7426c90d8d6801d1b7d328 41fabb080f831f05e555112c040482a1f500b70c1517c4f81e41aa1d54092b8e 4c0621a1a5cb64639e530706ae187862cd0886bc6da32746186dc82a0be56469 4f2e2df0cfe52ad44f7d4a84607536054ff6b7fc653152719f60867328aedf4f 51f0c20476c14e879a71c649826e0a48d78a8b7b26dad0029ee514abdba32e90 636a445be68622390c77e2d251e546580d460f1ca53ed39cb1739afc68b3cd64 696efc15b94f425925bdc6bee015a23718d18f3838287fb906cfc4ccc0ffa887 81348ba0b13fd617ab5127bbbc21b5fbced41400ed933cc438fe79fa75453682 83fba898df5dab1720ec6e402f5056c42792028c84056c9d3b3971823f49bc1d 840fd039b2509fb50b328c0b5ada8c7300608e57bce8ce1bce822ee34b23fa52 854d48bcc399be41e357f14b551aaf5d84481971932e2ebad3b9a213d95e0101 87054757a431e9d123829c5e5c357efe934d5bccf80b51f107c34df903cc198e 8cd7093915b08264160bd37a973f5cf8e11b5e61e419481edbf264f06a311088 92b04da46ffb7318b1b0eb42c203fabd859abd743cff4389b4eeb00d57941cf5 968be90244a7ff16d3b0b759e3ae26b4b6becf82de6d5da664d53a1041efeee2 97c1e9a931d70c1675533a5ca58c4035f4d7ffd295dd30be79a62d7d58bcde1c a9b1b3bfeec9a35fccb8a805f149cbe50e7ff9f3e0732e237f5ff937e38e8f9b b8d2bea73a19c2dd257bb31288cf7a2e44e22ae0f047adb90f8cb5f6dd0462d2 babc7a17f4a78acbea5687871dcd2c0e7b76ec2dd118bc96f589f1d5c9e3ec4f d99f067016eb476b3cc96b2d9ad17597a3cd0138375536ee26e017c78f9113ab e06ae6061d743b928171b459105e939917f387b043ef91d4000d518415f8a958 e15d354c385a065f8c01fb2b7df37fffe7d80dc3a6767480f05893f5939024a9 e2e1a7f638f85139b9188e1c60d47a7832a0b3388dfa0269583e89924fa4f47e f3cadf4e43b13f9ed7ad0325c6ec27aa52046a8ad5858e70143f82ed6d177d51 f86dd4bc66540323fdd88ec058be87f1535be2cd6843846453b59cfc1f8bb1ae

Affected versions of NightOwl are signed with the following Team Identifier:

TPE-FYI, LLC (7J27HUBW2X)

Apple recently revoked the developer’s code-signing certificate.

Note that older versions of NightOwl, prior to its sale, are code-signed with a Team Identifier belonging to Benjamin Kramser (2AVLWWC6KL). Antivirus software should not detect these files as malicious.

If installed, NightOwl’s components can be found at the following locations:

/Applications/NightOwl.app ~/Library/LaunchAgents/NightOwlUpdater.plist

Note that ~ indicates the current user’s home directory, for example /Users/username. If you have multiple user accounts on an affected system, you may need to check for the LaunchAgent plist file in those accounts as well.

The following domain and subdomains have reportedly been used by affected NightOwl versions to tunnel communications over SSH:

*.squidyproxy[.]com proxy-api1.squidyproxy[.]com proxy-gw1-europe.squidyproxy[.]com

This domain was registered in early April 2022, approximately seven months before TPE.FYI LCC acquired NightOwl.

Network administrators can check recent network traffic logs to try to identify whether any computers on their network may have attempted to contact this domain or any subdomain thereof. Its presence in logs could indicate that a Mac on the network may have an affected version of NightOwl installed.

Do security vendors detect this by any other names?

Other antivirus vendors’ names for various components of affected versions of NightOwl may include variations of the following:

A Variant Of OSX/HackTool.Chisel.A, A Variant Of OSX/IPRoyal.Pawns.A Potentially Unwanted, A Variant Of OSX/Packed.Obfuscated.A Suspicious, ABRisk.ZWCO-7, Adware/Chisel!OSX, Adware/IPRoyal_Pawns!OSX, Application.Mac.Agent.IS (B), Application.MAC.Generic.1621 (B), Backdoor:MacOS/Multiverze, HackTool:MacOS/Chisel.A!MTB, Hacktool.OSX.Chisel.3!c, HEUR:Backdoor.OSX.Sliver.gen, HEUR:HackTool.OSX.Agent.q, HEUR:Trojan-Proxy.OSX.Agent.gen, HEUR:Trojan.OSX.Agent.gen, Heuristic.HEUR/OSX.MalSource.coekb, Heuristic.HEUR/OSX.MalSource.ejnsf, Heuristic.HEUR/OSX.MalSource.gzsbj, heuristic/HEUR/OSX.MalSource.zfkkg, MacOS:Chisel-A [PUP], Malware.OSX/Agent.epnfc, Malware.OSX/Agent.ichko, Malware.OSX/Agent.jbpzj, Malware.OSX/Agent.kciip, Malware.OSX/Agent.mzltd, Malware.OSX/Agent.ofrgi, Malware.OSX/Agent.qwkuf, Malware.OSX/Agent.whlfq, Malware.OSX/Agent.wojiw, Malware.OSX/AVI.Agent.muate, Malware.OSX/AVI.Agent.pxing, Malware.OSX/Sliver.igtnf, Not-a-virus:HEUR:Server-Proxy.OSX.Chisel.a, Not-a-virus:HEUR:Server-Proxy.OSX.Monetizer.c, Not-a-virus:HEUR:Server-Proxy.OSX.Monetizer.d, Not-a-virus:UDS:Server-Proxy.OSX.Monetizer, Osx.Server-Proxy.Chisel.Jajl, Osx.Server-Proxy.Chisel.Vwhl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Cdhl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Etgl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Gkjl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Hajl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Lajl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Lqil, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Msmw, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Nsmw, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Osmw, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Pgil, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Rwhl, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Sgil, Osx.Trojan.Agent.Vwhl, OSX.Trojan.Gen.2, Osx.Trojan.Sliver.Vgil, OSX/Agent-BKCU, OSX/Agent.fs, OSX/Agent.gen, OSX/Chisel.ext, Other:PUP-gen [PUP], Packed:MacOS/Obfuscated.1e476793, Program:MacOS/Multiverze, Program.APPL/GM.Agent.BK, Program.APPL/GM.Pawns.LS, ProxyTool:MacOS/Monetizer.c, PUA:Win32/Puwaders.C!ml, PUA:Win32/Vigua.A, PUA.Generic, Riskware.OSX.Monetizer.1!c, Riskware.OSX.Pawns.1!c, Riskware.ZIP.Monetizer.1!c, Riskware/Application!OSX, Static AI – Suspicious Mach-O, Trojan:MacOS/Multiverze, Trojan:Win32/Vigorf.A, Trojan.MAC.Generic.112645 (B), Trojan.OSX.Agent.4!c, Trojan.OSX.Generic.4!c, Trojan.OSX.Poseidon, Trojan.OSX.Psw, Trojan.OSX.Sliver.4!c, Trojan.ZIP.Generic.4!c, virus/OSX/Agent.epnfc, virus/OSX/Agent.illay, virus/OSX/Agent.udgyc, virus/OSX/Agent.uppvw

How can I learn more?

For additional technical details about the NightOwl kerfuffle, you can read Taylor Robinson’s original write-up from June 28.

Each week on the Intego Mac Podcast, Intego’s Mac security experts discuss the latest Apple news, including security and privacy stories, and offer practical advice on getting the most out of your Apple devices. Be sure to follow the podcast to make sure you don’t miss any episodes.

You can also subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and keep an eye here on The Mac Security Blog for the latest Apple security and privacy news. And don’t forget to follow Intego on your favorite social media channels: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()